This weekend, in the co-main event of the Ultimate Fighting Championship’s inaugural event on an ESPN platform, former NFL player Greg Hardy will do battle. He is a former NFL player in part because of a 2014 domestic assault conviction (later overturned and expunged from his record), which led to an investigation by the League, which concluded that there was “sufficient credible evidence” that Hardy had used physical force on at least four occasions against his ex-girlfriend. Although he initially received the support of both teams he played for — the Carolina Panthers and Dallas Cowboys — his playing career came to an end in 2015, at the conclusion of his Cowboys contract.

Less than two years later he made his MMA debut in a November 4th amateur bout, and now, 14 months later, he will be fighting for the biggest organization in mixed martial arts, in one of the card’s feature bouts. The discussion around Hardy’s signing has not been without contention, as UFC President Dana White has gone to bat for his 30-year-old signee, and together, they have weathered the criticism that has been directed at the fighter and the organization that employs him. And as the discussion moves from hand-wringing from fans to hand-slinging from fighters, we should see a familiar word make its way into the discourse: REDEMPTION.

Hardy is far from the first professional athlete to be beset by accusations, charges, or convictions for violence against women. And indeed, as the “Me Too Era” becomes more ubiquitous in the national lexicon, Hardy is only one of the countless examples of so-called “toxic masculinity” in action, involving men of every age, race, and social station. These are familiar narratives, and yet the redemption subplot is often the one we fixate on. How may one “pay a price,” then find a path back to societal acceptance? How are his sins cleansed? How long does it take? How soon can he come back once exiled? How does he prove he’s “learned his lesson?”

From the perspective of pop culture, the clock is always ticking — we’re always looking to move to the next new story. So the story of the great man felled by wrongdoing isn’t nearly as exciting as that same man making his way back to his feet and putting things back on track. Strained metaphor aside, adversity compels, and triumph in the face of it is a story that sells.

But whose triumph? Our Hardys, our Derrick Roses, and our Louis CKs are all positioned as the protagonists in their narratives — their victims, typically nameless, simply become their adversities. And we often judge whether they overcome that adversity not in terms of how much good they do, but simply how good they do. If you are a musician, hit the studio hard and crank out hit records. If you are a comedian, make people laugh so hard that they forget uncomfortable truths. If you are a professional athlete, excel on the field or the court or the canvas, and win.

But whose triumph? Our Hardys, our Derrick Roses, and our Louis CKs are all positioned as the protagonists in their narratives — their victims, typically nameless, simply become their adversities. And we often judge whether they overcome that adversity not in terms of how much good they do, but simply how good they do. If you are a musician, hit the studio hard and crank out hit records. If you are a comedian, make people laugh so hard that they forget uncomfortable truths. If you are a professional athlete, excel on the field or the court or the canvas, and win.

But the redemption story is so alluring that it pushes out other narratives. On the same UFC card as Hardy is Rachael Ostovich, a female mixed martial artist who was once known for her penchant for wearing Wonder Woman costumes to weigh-ins. 1-1 in the UFC, she hasn’t shown nearly the promise in the flyweight division as the heavyweight Hardy has in his brief career. Last November, she was the victim of a violent assault at the hands of her husband. The details are too triggering to detail, and the pictures to grisly to share. Just two months after her attack, she will be fighting in the UFC’s Octagon; she will be triumphing over adversity just by stepping in to compete. But her story has to intertwine with Hardy’s, and in many ways be overshadowed by it. From her alleged “permission” given for Hardy to fight (permission that was requested by someone who is trying to make a LOT of money from Hardy), to the assurances she has made in the run-up to this card that “there’s no negative” concerning Hardy, there’s still the sense that she isn’t centered in her narrative. (And this piece is no exception, as it isn’t really about her either.)

In a perfect world, our narratives around men “brought down” by wrongdoing would be secondary to narratives or healing and overcoming for their victims. But winning, losing, and the excellence of athletic performances is obviously the province of sport, and Greg Hardy will be fighting on Saturday night — not his victim. However, there’s something a little unsettling about the idea that the course of how his story gets told will hinge on how well he can perform violence on a high-profile stage. For many fans, him being an elite talent is as far as the story needs to go. For others, the redemption story is something to root for (or against), and a win in the cage is a win in life. ESPN and the UFC are banking on our emotional investment in this fight, our sense of the stakes for the fighter, to attract the attention of the audience. And it will probably yield dividends. But the flipside of our desire to see that payoff is that we can more readily move on from the uncomfortable parts of the story. It would be better if we took the time to grapple with them.

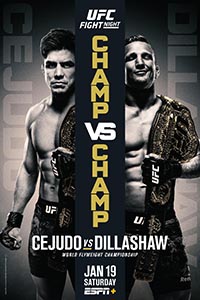

UFC on ESPN+ 1 |

UFC on ESPN+ 1: Cejudo vs. Dillashaw takes place January 19, 2019 at Barclays Center in Brooklyn, New York.

|