Everyone knows that the UFC needs to make stars in 2012. Here are five mechanisms that are essential in the star-making process.

The first part of this series focused on what it takes to be a star in the current UFC era. However, the process by which stars are made needs to be scrutinized and analyzed as well. Even a potential star who possesses mass appeal needs to reach those masses in ways that suit them. But MMA is not pro wrestling, where stars can be created out of whole cloth because management takes a liking to you. Having said that, the development of athletes into superstars can not be completely organic, and happen without some degree of investment in that process. And currently there are five main mechanisms by which an environment conducive to star-making can be cultivated:

1. Fox

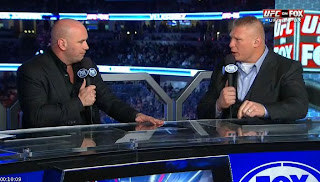

The Fox Network by far is the most effective means at the UFC’s disposal to reach mainstream sports fans on a consistent basis. Its football coverage is highly-rated, and its baseball coverage is comprehensive. By offering four fight cards a year on the network, the UFC is giving its athletes unprecedented visibility, as well as a platform to introduce and reinforce notions of stakes and significance for upcoming matchups. Its debut broadcast saw a title change, Brock Lesnar hamming it up in the studio, and Dana White appearing miscast and over his head in the role of “analyst.”

The Fox Network by far is the most effective means at the UFC’s disposal to reach mainstream sports fans on a consistent basis. Its football coverage is highly-rated, and its baseball coverage is comprehensive. By offering four fight cards a year on the network, the UFC is giving its athletes unprecedented visibility, as well as a platform to introduce and reinforce notions of stakes and significance for upcoming matchups. Its debut broadcast saw a title change, Brock Lesnar hamming it up in the studio, and Dana White appearing miscast and over his head in the role of “analyst.”

Yet further forays into the relationship should allow for the UFC to give its best and most promising talents the opportunity to ply their trade in front of millions of viewers. Furthermore, much like Brock Lesnar’s positioning as analyst allowed him to both offer insight into the upcoming contest and hype a showdown with the winner, the Fox Studios set should offer champions and contenders the opportunity to put their own sense of their talents and importance into focus. Jon Jones, for instance, has a potential date with the winner of Evans-Davis, and Dan Henderson, who has fought Michael Bisping, trained with Chael Sonnen, and who too would like a shot at the champion Jones, could both be valuable in-studio, introducing themselves to the larger network audience, while showing themselves to be erudite, affable, and entertaining,

Another way of utilizing the Fox relationship that has been less than fully-explored is through highlight packages. Fans of mainstream sports are used to seeing 30- or 60-second clips set to music that catch them up on results, while also putting into focus the storylines that they need to be kept appraised of. Fans who would be unwilling to spend three hours watching “no-name” fighters compete on an undercard could be very engaged by a three-minute clip of the most exciting moments of that undercard’s results. Viewers who don’t feel like hitting up Wikipedia, Sherdog, and YouTube to see the entire body of a fighter’s Octagon performances would however respond to a 60-second recap of the essentials of his UFC career, including awesome finishes, flashy offense, and a brief encapsulation of his accomplishments to date. This wouldn’t be to set up any future fights, but simply to provide an easily-digestible means of giving the home viewer important information about who the major players in a given division might be. Once the prominent names have been introduced to fans, the next question is whether their potential will be realized. Either way, the fans will be paying attention as that question is answered.

2. Prominence & Ubiquity

Perception is often reality. If you treat someone like A Big Deal, it isn’t long before people start to believe that that individual is one. There are now 7 UFC World Champions (soon to be 8), and only a few of them are actually treated like something special. And one of them is GSP, who will be out of sight (and likely out of mind) for the better part of 2012. Being the best fighter in the world at a particular weight class is something to be proud of, yet if the UFC doesn’t feature those fighters prominently, then the subtle message being sent is that it’s okay to overlook them. Jose Aldo, Dominick Cruz, and Frankie Edgar should be appearing on UFC programming as often as possible; if they aren’t exposed, then their top contenders won’t be either. And fighters who are expected to be future champions should also be prominently featured.

Perception is often reality. If you treat someone like A Big Deal, it isn’t long before people start to believe that that individual is one. There are now 7 UFC World Champions (soon to be 8), and only a few of them are actually treated like something special. And one of them is GSP, who will be out of sight (and likely out of mind) for the better part of 2012. Being the best fighter in the world at a particular weight class is something to be proud of, yet if the UFC doesn’t feature those fighters prominently, then the subtle message being sent is that it’s okay to overlook them. Jose Aldo, Dominick Cruz, and Frankie Edgar should be appearing on UFC programming as often as possible; if they aren’t exposed, then their top contenders won’t be either. And fighters who are expected to be future champions should also be prominently featured.

There are many excuses for putting a promotion’s star out at the forefront. A fight in his weight class is being contested, and he could be shown on camera reacting to the fight, or otherwise “scouting” future opposition. Two top 10 contenders do battle, and he could be interviewed cageside to offer his insight into the outcome, and his own assessment of the fighters. Even if he already has a fight booked, commentators should constantly be tying the champion and the most high-profile contenders to the rest of the division, to reinforce the notion that these fighters are A Big Deal, even when a given fight might not appear to be.

3. UFC Primetime

The three-part “UFC Primetime” documentary series has done an amazing job of not only showing the human side of Georges St. Pierre and his challengers BJ Penn, Jake Shields and Dan Hardy, but their larger-than-life qualities as well. Additional series like Cain Velasquez vs. Brock Lesnar and “Rampage” Jackson vs. Rashad Evans managed to cast the struggles between two fighters as something existential, something epic. That’s the appeal of the Primetime medium; it adds a level of grandeur and gravitas to a fight, and with very few exceptions, fighters who pass through the series end up bigger stars because of it.

The three-part “UFC Primetime” documentary series has done an amazing job of not only showing the human side of Georges St. Pierre and his challengers BJ Penn, Jake Shields and Dan Hardy, but their larger-than-life qualities as well. Additional series like Cain Velasquez vs. Brock Lesnar and “Rampage” Jackson vs. Rashad Evans managed to cast the struggles between two fighters as something existential, something epic. That’s the appeal of the Primetime medium; it adds a level of grandeur and gravitas to a fight, and with very few exceptions, fighters who pass through the series end up bigger stars because of it.

In the coming year, there will be a number of fights that will warrant the Primetime treatment, and although the cost of producing it is a bit on the high side, the potential benefits far outweigh those costs. Four to six Primetime series would run the company four to six million dollars, but considering its capacity to double a potential pay-per-view buyrate, they are investments worth making.

4. The Ultimate Fighter

If UFC Primetime is about a short period of focused and concentrated hype, aided by grandeur and gravitas, then The Ultimate Fighter is its polar opposite. Over 12 weeks, mundane minutae is mined to build a conflict over time to a boiling point. Where Primetime endeavors to make its subjects larger than life, TUF brings them down to the level of reality television stars, at their petty, self-absorbed worst. TUF has a sprawling cast of characters which it introduces to fans, and the twists and turns are meant to keep you coming back each week, as you learn a little bit more about the fighters, and begin to draw your conclusions about who to root for and who to root against. Having said all that, TUF has a track record of success that cannot be denied. Fighters like Forrest Griffin, Josh Koscheck, Chris Leben, Rashad Evans, and Michael Bisping are still defined by the way they came across on the show, for better or worse. And we’ve seen the coaching stints of BJ Penn, Tito Ortiz, and Matt Hughes turn fan opinion around 180 degrees.

If UFC Primetime is about a short period of focused and concentrated hype, aided by grandeur and gravitas, then The Ultimate Fighter is its polar opposite. Over 12 weeks, mundane minutae is mined to build a conflict over time to a boiling point. Where Primetime endeavors to make its subjects larger than life, TUF brings them down to the level of reality television stars, at their petty, self-absorbed worst. TUF has a sprawling cast of characters which it introduces to fans, and the twists and turns are meant to keep you coming back each week, as you learn a little bit more about the fighters, and begin to draw your conclusions about who to root for and who to root against. Having said all that, TUF has a track record of success that cannot be denied. Fighters like Forrest Griffin, Josh Koscheck, Chris Leben, Rashad Evans, and Michael Bisping are still defined by the way they came across on the show, for better or worse. And we’ve seen the coaching stints of BJ Penn, Tito Ortiz, and Matt Hughes turn fan opinion around 180 degrees.

However, recent seasons of The Ultimate Fighter have been met with widespread apathy, even as their ratings have remained relatively stable. It is possible, though, that the format change and relaunch on a new network will rejuvenate the show, and the fan base’s opinion of it. If that happens, then we can expect Zuffa to make full use of the show as a tool for introducing up and comers, and stoking the fires on feuds that it feels need just that little bit extra to put them over the top.

5. Sponsorship

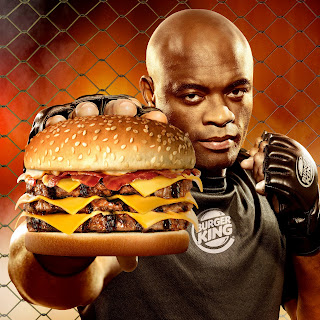

The final component is perhaps the most elusive, because it involves Other People’s Money. Every major sports league and confederated entity has official sponsorships that it relies upon in a synergistic way to legitimize it and its commercial viability. The stars that appear in such spots are usually chosen by both the leagues and their sponsors, with an eye towards their shared notions of marketability. However, there are other sponsors who have formed relationships with individual athletes separate from any association with the league. While it may be tempting for a UFC fighter to let the organization pursue blue chip sponsorship opportunities, consider the fact that the biggest and most mainstream of Georges St. Pierre’s sponsorships — Gatorade and Under Armour — were secured not by the Zuffa Publicity Machine, but by GSP’s management. Fighters on the verge of stardom need to pursue their own branding initiatives, and Zuffa needs to be supportive of those endeavors, especially without insisting that its brand significance be pushed to the forefront, overshadowing those efforts.

The final component is perhaps the most elusive, because it involves Other People’s Money. Every major sports league and confederated entity has official sponsorships that it relies upon in a synergistic way to legitimize it and its commercial viability. The stars that appear in such spots are usually chosen by both the leagues and their sponsors, with an eye towards their shared notions of marketability. However, there are other sponsors who have formed relationships with individual athletes separate from any association with the league. While it may be tempting for a UFC fighter to let the organization pursue blue chip sponsorship opportunities, consider the fact that the biggest and most mainstream of Georges St. Pierre’s sponsorships — Gatorade and Under Armour — were secured not by the Zuffa Publicity Machine, but by GSP’s management. Fighters on the verge of stardom need to pursue their own branding initiatives, and Zuffa needs to be supportive of those endeavors, especially without insisting that its brand significance be pushed to the forefront, overshadowing those efforts.

Perhaps the most egregious example of the UFC overshadowing a future star in recent memory is the Bud Light spot featuring Jon Jones, where UFC President Dana White on more than one occasion positioned himself as the Alpha Male, getting the last word in (the catchphrase even), having the camera focus on him, and worst of all, giving the UFC Light Heavyweight Champion the infamous “C’mon Nod,” literally leading a man he’d like to one day promote as the Baddest Man on the Planet out of the frame. These are subtleties, but that’s precisely what makes them a particularly insidious form of undercutting. The star is the man who commands attention when he enters and leaves a room, not the man who plays wingman to the older bald guy, and responds to the C’mon Nod.

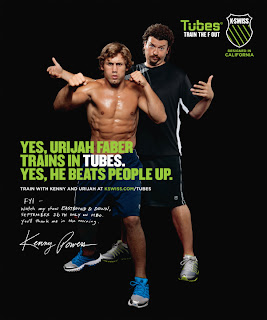

In contrast, commercials featuring Urijah Faber leave no doubt about his star status. He is always the focal point, whether he is promoting the Versus network, No Fear, Amp Energy Drink, or K-Swiss, alongside the Kenny Powers character from the “Eastbound and Down” television series. The consistency with which he is portrayed as a Big Deal mirrors the way that star professional athletes in other sports are treated, and as such, is just as effective at introducing and reinforcing Urijah Faber as Someone to Pay Attention To, i.e., a Star. Again, this is not something that the UFC can always facilitate or dictate, nor should coaching fighters to be media savvy be prioritized above coaching to become better, more well-rounded, fighters. However, those fighters who take the initiative to build their brands, secure national sponsors, and increase their visibility beyond the narrow demographic of fight fans should not be made to feel like they are not team players. Furthermore, those fighters should be embraced as the assets that they are to the promotion. After all, the reach of the Zuffa Promotional Machine only extends so far, and anytime a fighter can expand that reach, profits for the company can be realized. Beyond that, when a UFC fighter becomes a legitimate star, other fighters believe that they can be that next star, which makes it easier to attract and retain top talents, who need the highest-profile stage to realize their star potential.

In contrast, commercials featuring Urijah Faber leave no doubt about his star status. He is always the focal point, whether he is promoting the Versus network, No Fear, Amp Energy Drink, or K-Swiss, alongside the Kenny Powers character from the “Eastbound and Down” television series. The consistency with which he is portrayed as a Big Deal mirrors the way that star professional athletes in other sports are treated, and as such, is just as effective at introducing and reinforcing Urijah Faber as Someone to Pay Attention To, i.e., a Star. Again, this is not something that the UFC can always facilitate or dictate, nor should coaching fighters to be media savvy be prioritized above coaching to become better, more well-rounded, fighters. However, those fighters who take the initiative to build their brands, secure national sponsors, and increase their visibility beyond the narrow demographic of fight fans should not be made to feel like they are not team players. Furthermore, those fighters should be embraced as the assets that they are to the promotion. After all, the reach of the Zuffa Promotional Machine only extends so far, and anytime a fighter can expand that reach, profits for the company can be realized. Beyond that, when a UFC fighter becomes a legitimate star, other fighters believe that they can be that next star, which makes it easier to attract and retain top talents, who need the highest-profile stage to realize their star potential.

Perhaps it’s only fitting that in 2012, the UFC, untethered to the familiar teat of Spike TV, is not only blazing a new and unfamiliar path forward on Fox, but is also forced to make due without its most dependable PPV draws. This situation has forced them to reevaluate old paradigms, and recognize that this new beginning hungers for new stars to usher the sport forward. The 2012 UFC can discover and develop stars that the 2007 UFC could not. The 2012 UFC can offer its stars the ability to be seen by tens of millions all around the world, and be recognized as legitimate sportsmen. The 2012 UFC can see its stars pitching main stream products, and standing alongside the stars of other sports on equal footing. It’s a New Day, and let’s hope that the UFC’s eyes are wide open to all the ways that they, and the fighters under their banner, can seize it.

I disagree with the entire premise "Everyone knows that the UFC needs to make stars in 2012."